Dans une note publiée le 23 mars 2021 et intitulée «Et maintenant?», je faisais référence à un article publié sur le site web Reykjavik Grapevine qui posait les questions habituelles auxquelles personne ne peut répondre quand se produit une éruption : combien de temps cette éruption va-t-elle durer? Quelle forme pourrait-elle prendre? L’écrivais que de telles prévisions étaient extrêmement hasardeuses.

Dans une note publiée le 23 mars 2021 et intitulée «Et maintenant?», je faisais référence à un article publié sur le site web Reykjavik Grapevine qui posait les questions habituelles auxquelles personne ne peut répondre quand se produit une éruption : combien de temps cette éruption va-t-elle durer? Quelle forme pourrait-elle prendre? L’écrivais que de telles prévisions étaient extrêmement hasardeuses.

Pourtant, il est une question beaucoup plus pratique que l’on est en droit de se poser alors que l’éruption se poursuit dans la Geldingadalur : peut-elle devenir une menace pour les zones habitées?

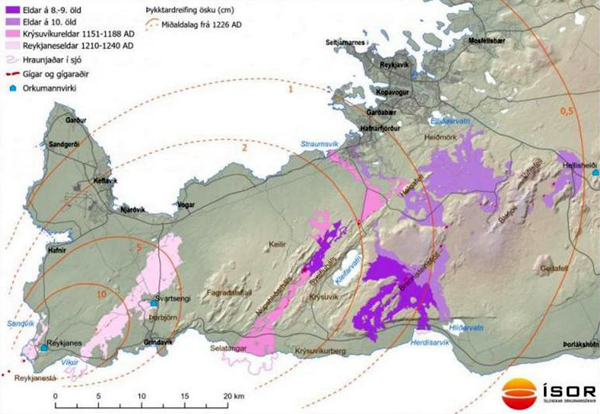

S’agissant de l’éruption proprement dite, il est possible que les deux spatter cones (voir capture d’écran ci-dessous) qui laissent échapper la lave fusionnent pour n’en former qu’un seul si l’activité intense persiste dans l’un d’eux. En ce moment, le débit d‘émission de la lave est d’environ 5 mètres cubes par seconde. À ce rythme, les volcanologues islandais pensent que la lave pourrait commencer à sortir de la Geldingadalur d’ici 8 à 18 jours. Cependant, si le débit augmente, ce temps pourrait être raccourci.

Si la lave commence à sortir de la Geldingadalur, elle se dirigera probablement vers la vallée voisine de Meradalir, puis vers Nátthagi au sud. Si elle s’échappe de Nátthagi, elle continuera probablement sa course vers le sud, et il se pourrait même qu’elle atteigne la route côtière, sans toutefois menacer des zones habitées.

Ces projections dépendent, bien sûr, du débit à la source, mais aussi de la durée de l’éruption. Pour le moment, il n’y a aucun signe que la lave ralentisse. Je garde à l’esprit qu’au début de l’éruption, les scientifiques islandais pensaient qu’elle ne durerait que quelques jours. Cependant, de nouvelles données les ont fait changer d’avis !! Errare humanum est ! Ces mêmes scientifiques pensent maintenant que le magma provient d’une profondeur de 15 à 20 kilomètres. Comme il n’y a pas eu d’éruption sur la péninsule de Reykjanes depuis des lustres, ils pensent qu’une grande quantité de magma est peut-être stockée sous la surface. Si c’est le cas, l’éruption pourrait durer un temps considérable. Mais personne ne le sait!

Source: Reykjavik Grapevine.

————————————————

In a post released on March 23rd 2021 and entitled “What next?”, I referred to an article published on the Reykjavik Grapevine website that asked the usual questions that nobody is able to answer: how long will this eruption go on? What shape could it take? I wrote that making predictions about the future of the current eruption is quite hazardous.

In a post released on March 23rd 2021 and entitled “What next?”, I referred to an article published on the Reykjavik Grapevine website that asked the usual questions that nobody is able to answer: how long will this eruption go on? What shape could it take? I wrote that making predictions about the future of the current eruption is quite hazardous.

A more practical question is being asked now the eruption is going on: Can it become a threat to populated areas?

As far as the eruption is concerned, the possibility exists that the two spatter cones (see screenshot below) through which lava is flowing could merge into one due to increased activity in one of the craters. The current lava output is about 5 cubic metres per second. At this rate, Icelandic volcanologists think lava could begin making its way out of the valley in anywhere from eight to 18 days. However, should the output increase, this time could be reduced.

If lava starts travelling out of Geldingadalur, it will probably begin flowing into the neighbouring valley of Meradalir, and from there, to Nátthagi to the south.

If it begins to flow from Nátthagi, it will likely make its way south, where it might even reach the south coastal highway of Reykjanes but would not reach populated areas.

These projections obviously depend on the lava output, but also on how long the eruption will last. For the time being, there is no sign lava is slowing. I keep in mind that at the start of the eruption scientists believed that it would only last a few days. However, new data has made them change their minds!! Scientists now believe that the magma comes from a depth of 15-20 kilometres. AS there has been no eruption on the Reykjanes Peninsula for a very long time, there could be a great deal of magma in store beneath the surface, and this eruption might last a considerable amount of time. But nobody knows!

Source : Reykjavik Grapevine.