![]() La situation éruptive sur la péninsule islandaise de Reykjanes fai se poser beaucoup de questions aux scientifiques du Met Office islandais et de l’Université d’Islande. Faisant référence au soulèvement du sol dans la région de Svarsengi, qui est désormais plus important qu’avant les éruptions précédentes, ils ont d’abord déclaré qu’une éruption était imminente. Aujourd’hui, l’un des volcanologues vient de déclarer que si une éruption se produit sur la péninsule de Reykjanes, elle se déclenchera probablement vers le 20 mars 2025. Cependant, il souligne que « la prévision d’une éruption reste incertaine, et il est également possible que du magma s’accumule à l’ouest du lac Kleifarvatn ».

La situation éruptive sur la péninsule islandaise de Reykjanes fai se poser beaucoup de questions aux scientifiques du Met Office islandais et de l’Université d’Islande. Faisant référence au soulèvement du sol dans la région de Svarsengi, qui est désormais plus important qu’avant les éruptions précédentes, ils ont d’abord déclaré qu’une éruption était imminente. Aujourd’hui, l’un des volcanologues vient de déclarer que si une éruption se produit sur la péninsule de Reykjanes, elle se déclenchera probablement vers le 20 mars 2025. Cependant, il souligne que « la prévision d’une éruption reste incertaine, et il est également possible que du magma s’accumule à l’ouest du lac Kleifarvatn ».

Le scientifique ajoute que si une éruption se produit, elle suivra probablement le schéma familier des événements passés ; elle commencera au mont Stóra-Skógfell avant que des fissures progressent dans une ou les deux directions. « L’éruption pourrait durer plusieurs jours, voire plusieurs semaines. »

Le volcanologue pense également que les éruptions le long de la chaîne de cratères Sundhnúkagígar sont sur le point de se terminer. « L’activité éruptive du mont Fagradalsfjall a duré pendant environ deux ans avant de se déplacer vers Sundhnúkagígar il y a un peu plus d’un an. Ces deux éruptions ont montré des différences ; par exemple, il y a eu moins d’inflation au mont Fagradalsfjall. Aujourd’hui, le cycle éruptif actuel semble se terminer, et je suis persuadé que les volcans de Sundhnúkar vont terminer leur activité cette année. »

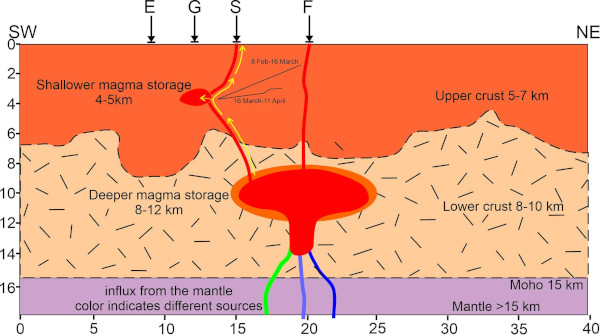

Bien que le prochain essaim sismique puisse commencer à tout moment, son emplacement exact reste inconnu. Deux essaims dans les secteur de Krysuvik, à l’ouest du lac Kleifarvatn, les 7 et 9 mars 2025 indiquent que du magma s’accumule peut-être dans la région. Le volcanologue du Met Office déclare : « Le fait que ces événements se produisent à cinq kilomètres de profondeur laissent supposer que du magma s’accumule sous la région. Cela pourrait éventuellement conduire à une éruption dans le secteur, bien qu’il soit impossible de dire si cela se produira cette année, dans dix ans ou dans vingt ans. »

Il convient de noter qu’un autre scientifique du Met Office a interprété différemment l’activité sismique dans la région de Krysuvik. « L’activité sismique à Krýsuvík n’est pas liée aux événements sur la chaîne de cratères de Sundhnúkagígar. Les essaims sismiques sont un phénomène naturel dans la région ; ils se produisent environ toutes les une à deux semaines. La péninsule de Reykjanes est connue pour son activité sismique périodique due au mouvement de la dorsale médio-atlantique, où les plaques tectoniques eurasienne et nord-américaine se rencontrent. » On peut aussi lire dans l’Iceland Monitor : « Les scientifiques continuent d’observer ces schémas pour évaluer tout changement potentiel de l’activité volcanique ou hydrothermale, d’autant plus qu’une nouvelle éruption à Reykjanes pourrait survenir à tout moment. »

Comme le disait le regretté François Le Guern au début de ses conférences : »Je ne sais pas, nous ne savons pas prévoir les éruptions volcaniques ».

Source : Met Office, Iceland Review, Iceland Monitor.

Krysuvik site d’une prochaine éruption? (Photo: C. Grandpey)

————————————————–

![]() The eruptive situation on the Reykjanes Peninsula in Iceland is puzzling scientists at the Icelandic Met Office and at the University of Iceland. Referring to the ground uplift in the Svarsengi area which is now more significant than before the previous eruptions, they first said that an eruption was imminent. Today, one of the volcanologists says that if an eruption occurs on the Reykjanes Peninsula, it is most likely to happen around March 20th, 2025. However, he emphasizes that »predicting an eruption remains uncertain, and it is still possible that magma is accumulating west of Kleifarvatn Lake. »

The eruptive situation on the Reykjanes Peninsula in Iceland is puzzling scientists at the Icelandic Met Office and at the University of Iceland. Referring to the ground uplift in the Svarsengi area which is now more significant than before the previous eruptions, they first said that an eruption was imminent. Today, one of the volcanologists says that if an eruption occurs on the Reykjanes Peninsula, it is most likely to happen around March 20th, 2025. However, he emphasizes that »predicting an eruption remains uncertain, and it is still possible that magma is accumulating west of Kleifarvatn Lake. »

The sacientist suggests that if an eruption does occur, it will likely follow the familiar pattern of past events, beginning at Mt. Stóra-Skógfell before cracks extend in one or both directions. »The eruption could last for several days or even weeks. » The scientist also believes that eruptions in the Sundhnúkagígar crater row are nearing their conclusion. »The Mt. Fagradalsfjall volcanoes were active for about two years before activity shifted to Sundhnúkagígar just over a year ago. These two eruptions have shown differences ; for instance, we saw less inflation at Mt. Fagradalsfjall. Now, the current eruption cycle appears to be winding down, and I firmly expect that the Sundhnúkar volcanoes will finish their activity this year. »

While the next seismic swarm could begin at any time, its exact location remains unknown. Two earthquake swarms west of Kleifarvatn Lake on March 7th and 9th suggest that magma may be accumulating in the area. The Met Office’s volcanologist says : »The fact that these quakes are occurring five kilometers deep suggests magma is accumulating beneath. This could eventually lead to an eruption there, though whether that happens this year, in ten years, or in twenty is impossible to say. »

It should be noted that another scientist at th Met Office interpreted the seismic activity in the Krysuvik area differently. »The earthquakes in Krýsuvík are not related to the events in the Sundhnúkagígar series. Seismic swarms are a natural occurrence in the area, happening roughly every one to two weeks. The Reykjanes Peninsula is known for its periodic earthquake activity due to the movement of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates meet. » One can also read in the Iceland Monitor : »Scientists continue to observe these patterns to assess any potential changes in volcanic or geothermal activity, especially in light of the fact that a new eruption in Reykjanes could occur at any time. »

As the late François Le Guern used to say at the beginning of his conferences : »I don’t know, we don’t know how to predict volcanic eruptions ».

Source : Met Office, Iceland Review, Iceland Monitor.