Un réchauffement stratosphérique soudain (en anglais Sudden Stratospheric Warming ou SSW) est un phénomène météorologique pendant lequel le vortex polaire dans l’hémisphère hivernal voit ses vents généralement d’ouest ralentir ou même s’inverser en quelques jours. Un tel phénomène va rendre le vortex plus sinueux, voire le rompre. Le changement est dû à une élévation de la température stratosphérique de plusieurs dizaines de degrés au-dessus du vortex. Elle grimpe très rapidement, passant de -70/-80°C à -10/-20°C degrés (soit une élévation d’une soixantaine de degrés en quelques jours). Pour rappel, la stratosphère est la couche atmosphérique située au dessus de celle où nous vivons – la troposphère – à une altitude située entre 10 et 50 km environ.

Un réchauffement stratosphérique soudain (en anglais Sudden Stratospheric Warming ou SSW) est un phénomène météorologique pendant lequel le vortex polaire dans l’hémisphère hivernal voit ses vents généralement d’ouest ralentir ou même s’inverser en quelques jours. Un tel phénomène va rendre le vortex plus sinueux, voire le rompre. Le changement est dû à une élévation de la température stratosphérique de plusieurs dizaines de degrés au-dessus du vortex. Elle grimpe très rapidement, passant de -70/-80°C à -10/-20°C degrés (soit une élévation d’une soixantaine de degrés en quelques jours). Pour rappel, la stratosphère est la couche atmosphérique située au dessus de celle où nous vivons – la troposphère – à une altitude située entre 10 et 50 km environ.

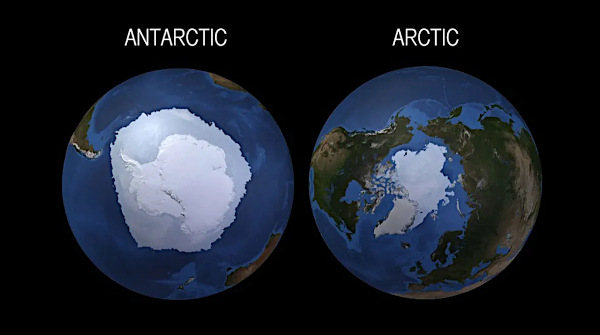

Durant un hiver habituel dans l’hémisphère nord, plusieurs événements mineurs de réchauffement stratosphérique se produisent, avec un événement majeur environ tous les deux ans. Dans l’hémisphère sud, les SSW semblent moins fréquents et moins bien compris.

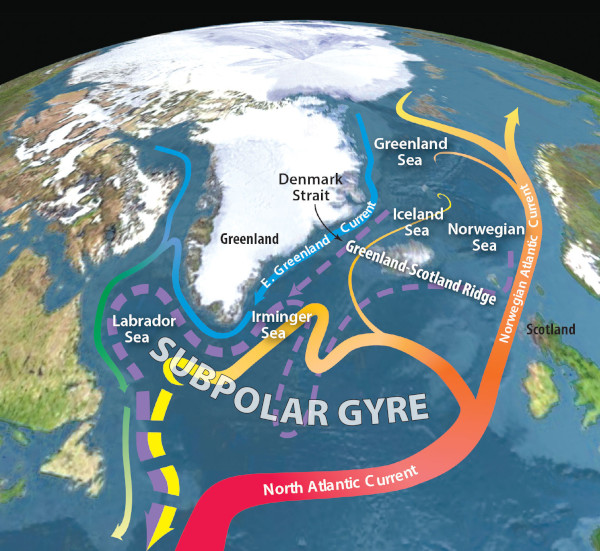

En conséquence, un réchauffement stratosphérique soudain et ses implications pour le vortex polaire peuvent avoir de sérieuses conséquences sur le climat de nos latitudes. L’air froid peut se retrouver piégé dans le jet stream (frontière entre l’air froid polaire et de l’air doux des tropiques) et être décalé jusqu’à nos latitudes, dans des régions peu habituées à un froid glacial, comme ce fut le cas en mars 2018 en Europe ou en février 2012 en France. Ces épisodes de SSW ne semblent toutefois pas avoir de relation avec le réchauffement climatique actuel ; ce sont de simples événements climatiques ponctuels.

°°°°°°°°°°

Les températures à haute altitude au-dessus du pôle Nord montent actuellement en flèche ; elles ont atteint 10°C en à peine une semaine. Ce réchauffement stratosphérique soudain perturbe le vortex polaire, ce qui pourrait avoir des conséquences importantes pour les conditions météorologiques dans l’hémisphère nord au mois de mars.

Cependant, le phénomène est encore mal compris et les scientifiques, bien qu’ils aient réussi à prévoir cet événement de réchauffement il y a deux semaines, disent qu’il est trop tôt pour savoir quel impact cela aura sur la météo dans les latitudes inférieures. Ces événements de réchauffement, qui se produisent en moyenne deux hivers sur trois, ne se déroulent pas toujours de la même manière.

Il se dit que l’événement actuel pourrait déclencher une réaction en chaîne qui chamboulerait les modèles météorologiques. Par exemple, l’est des États-Unis a connu des mois de janvier et de février exceptionnellement doux. Certains précédents réchauffements stratosphériques soudains accompagnés de perturbations du vortex polaire ont provoqué des vagues de froid extrêmes et de violentes tempêtes hivernales.

La dernière fois qu’un réchauffement stratosphérique soudain s’est produit, c’était le 5 janvier 2021. Un peu plus d’un mois plus tard, une vague d’air froid jamais vue depuis 1989 a plongé le centre des États-Unis dans une période de gel historique, provoquant la mise à l’arrêt du réseau électrique au Texas, un bilan de 330 morts, et plus de 27 milliards de dollars de dégâts.

Les scientifiques interrogés sur l’événement en cours disent qu’il est trop tôt pour savoir s’il déclenchera des conditions météorologiques extrêmes ou modifiera de manière significative les régimes météorologiques en cours dans l’hémisphère nord.

Les premiers jours du mois de mars s’annoncent froids en France, avec un épisode de vent de nord-nord-est d’une longueur inhabituelle. Reste à savoir si ces conditions météorologiques sont liées à un réchauffement stratosphérique soudain.

Source: Météo France,The Weather Channel.

En cliquant sur ce lien, vous aurez une très bonne explication (en anglais) du réchauffement stratosphérique soudain et du comportement du vortex polaire.

https://youtu.be/VnlFFaF_l7I

——————————————–

A Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW) is a meteorological phenomenon during which the polar vortex in the winter hemisphere sees its generally westerly winds slow down or even reverse within a few days. Such a phenomenon will make the vortex more sinuous, or even break it. The change is due to a rise of several tens of degrees in stratospheric temperature above the vortex. It climbs very quickly, going from -70 / -80 ° C to -10 / -20 ° C degrees (an increase of about sixty degrees in a few days). As a reminder, the stratosphere is the atmospheric layer located above the one where we live – the troposphere – at an altitude between 10 and 50 km approximately.

A Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW) is a meteorological phenomenon during which the polar vortex in the winter hemisphere sees its generally westerly winds slow down or even reverse within a few days. Such a phenomenon will make the vortex more sinuous, or even break it. The change is due to a rise of several tens of degrees in stratospheric temperature above the vortex. It climbs very quickly, going from -70 / -80 ° C to -10 / -20 ° C degrees (an increase of about sixty degrees in a few days). As a reminder, the stratosphere is the atmospheric layer located above the one where we live – the troposphere – at an altitude between 10 and 50 km approximately.

During a typical winter in the northern hemisphere, several minor stratospheric warming events occur, with one major event occurring approximately every two years. In the southern hemisphere, SSWs appear to be less frequent and less well understood.

As a result, sudden stratospheric warming and its implications for the polar vortex can have serious consequences for the climate of our latitudes. Cold air can get trapped in the jet stream (border between cold polar air and mild tropical air) and be shifted to our latitudes, in regions not used to freezing cold, like this was the case in March 2018 in Europe or in February 2012 in France. However, these episodes of SSW do not seem to have any relation to current global warming; they are simple one-off climatic events.

°°°°°°°°°°

Temperatures at the high altitudes above the North Pole are currently soaring, jumping up to 10°C in barely a week. This SSW is disturbing the polar vortex, which in turn could have major implications for weather patterns across the northern hemisphere in March.

However, the phenomenon is still poorly understood and scientists, despite successfully predicting this warming event two weeks ago, say it is too soon to know what it will mean for the weather in the lower latitudes. These events, which occur in two out of every three winters on average, don’t play out in a prescribed way.

There has been some speculation that the current event could trigger a chain reaction that would reshuffle weather patterns. For instance, the eastern U.S. has seen an exceptionally mild January and February and some previous sudden stratospheric warming and polar vortex disruptions have precipitated extreme cold snaps and severe winter storms.

The last time a sudden stratospheric warming event occurred was on January 5th, 2021. Just over a month later, the most dramatic cold air outbreak since 1989 plunged the central U.S. into a historic deep freeze, causing the collapse of Texas’s power grid, claiming at least 330 lives and incurring more than $27 billion in damages.

Multiple experts interviewed about the ongoing event say it’s too soon to know whether this one will trigger extreme weather or meaningfully change prevailing weather regimes over the northern hemisphere.

The first days of March are expected to be cold in France, with an unusually long episode of north-northeast winds. It remains to be seen whether these meteorological conditions are linked to a sudden stratospheric warming.

Source: Météo France,The Weather Channel.

By clicking on this link, you will get a very good explanation of the Sudden Stratospheric Warming and the behaviour of the polar vortex :

https://youtu.be/VnlFFaF_l7I

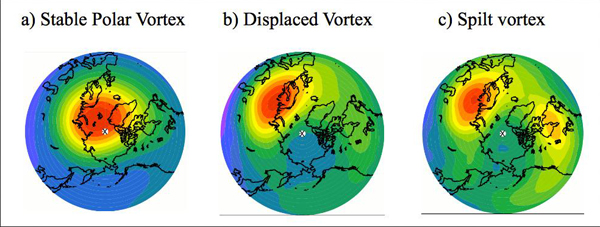

Variables de comportement du vortex polaire dans l’hémisphère nord : stable, décalé, rompu (Source: Met Office)

Un réchauffement stratosphérique soudain (en anglais Sudden Stratospheric Warming ou SSW) est un phénomène météorologique pendant lequel le vortex polaire dans l’hémisphère hivernal voit ses vents généralement d’ouest ralentir ou même s’inverser en quelques jours. Un tel phénomène va rendre le vortex plus sinueux, voire le rompre. Le changement est dû à une élévation de la température stratosphérique de plusieurs dizaines de degrés au-dessus du vortex. Elle grimpe très rapidement, passant de -70/-80°C à -10/-20°C degrés (soit une élévation d’une soixantaine de degrés en quelques jours). Pour rappel, la stratosphère est la couche atmosphérique située au dessus de celle où nous vivons – la troposphère – à une altitude située entre 10 et 50 km environ.

Un réchauffement stratosphérique soudain (en anglais Sudden Stratospheric Warming ou SSW) est un phénomène météorologique pendant lequel le vortex polaire dans l’hémisphère hivernal voit ses vents généralement d’ouest ralentir ou même s’inverser en quelques jours. Un tel phénomène va rendre le vortex plus sinueux, voire le rompre. Le changement est dû à une élévation de la température stratosphérique de plusieurs dizaines de degrés au-dessus du vortex. Elle grimpe très rapidement, passant de -70/-80°C à -10/-20°C degrés (soit une élévation d’une soixantaine de degrés en quelques jours). Pour rappel, la stratosphère est la couche atmosphérique située au dessus de celle où nous vivons – la troposphère – à une altitude située entre 10 et 50 km environ. A Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW) is a meteorological phenomenon during which the polar vortex in the winter hemisphere sees its generally westerly winds slow down or even reverse within a few days. Such a phenomenon will make the vortex more sinuous, or even break it. The change is due to a rise of several tens of degrees in stratospheric temperature above the vortex. It climbs very quickly, going from -70 / -80 ° C to -10 / -20 ° C degrees (an increase of about sixty degrees in a few days). As a reminder, the stratosphere is the atmospheric layer located above the one where we live – the troposphere – at an altitude between 10 and 50 km approximately.

A Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW) is a meteorological phenomenon during which the polar vortex in the winter hemisphere sees its generally westerly winds slow down or even reverse within a few days. Such a phenomenon will make the vortex more sinuous, or even break it. The change is due to a rise of several tens of degrees in stratospheric temperature above the vortex. It climbs very quickly, going from -70 / -80 ° C to -10 / -20 ° C degrees (an increase of about sixty degrees in a few days). As a reminder, the stratosphere is the atmospheric layer located above the one where we live – the troposphere – at an altitude between 10 and 50 km approximately.