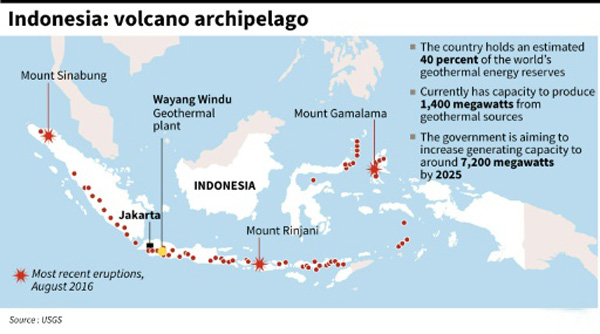

L’Indonésie, avec ses innombrables volcans, détient environ 40 pour cent des réserves géothermiques mondiales, mais le pays a pris beaucoup de retard dans leur exploitation. Aujourd’hui, le gouvernement indonésien a l’intention de multiplier par cinq la production géothermique dans la prochaine décennie, bien que les obstacles soient énormes dans un pays qui croule sous le fardeau de la paperasserie et où les grands projets sont souvent retardés, voire annulés.

L’Indonésie, avec ses innombrables volcans, détient environ 40 pour cent des réserves géothermiques mondiales, mais le pays a pris beaucoup de retard dans leur exploitation. Aujourd’hui, le gouvernement indonésien a l’intention de multiplier par cinq la production géothermique dans la prochaine décennie, bien que les obstacles soient énormes dans un pays qui croule sous le fardeau de la paperasserie et où les grands projets sont souvent retardés, voire annulés.

En Indonésie, la majeure partie de l’énergie électrique est générée à partir de ses abondantes réserves de charbon et de pétrole. A côté de cela, le pays a actuellement une capacité installée pour produire environ 1400 mégawatts d’électricité à partir de la géothermie. C’est suffisant pour fournir de l’énergie à 1,4 millions de foyers dans un pays où on en compte plus de 255 millions. Cela représente moins de cinq pour cent du potentiel géothermique estimé et place l’Indonésie loin derrière les deux principaux producteurs mondiaux que sont les États-Unis et les Philippines.

Toutefois, le gouvernement vise à accroître la capacité de production géothermique de l’Indonésie à près de 7200 mégawatts d’ici 2025, dans le cadre d’un plan plus vaste visant à stimuler le secteur des énergies renouvelables.

Le changement en matière de politique géothermique est dû à une nouvelle loi adoptée il y a deux ans et qui stipule que l’exploration géothermique n’est plus considérée comme une activité minière, comme c’était le cas auparavant. L’ancienne loi indiquait que l’industrie minière ne saurait être réalisée dans les vastes étendues de forêts protégées, censées contenir environ les deux tiers des réserves géothermiques de l’Indonésie.

Le gouvernement cherche également à amadouer les administrations locales en leur offrant jusqu’à un pour cent des recettes provenant de toute installation géothermique dans leur région.

Pourtant, les obstacles à la géothermie en Indonésie sont considérables. Bien que l’objectif prévu pour 2025 ne soit pas inaccessible, il sera extrêmement difficile à atteindre. L’un des problèmes les plus importants réside dans le coût d’exploration élevé. En effet, l’exploration de réserves géothermiques potentielles est une entreprise complexe qui demande beaucoup de temps et qui n’est pas toujours couronnée de succès. La construction d’une centrale géothermique coûte l’équivalent de 4 à 5 millions de dollars par mégawatt, contre 1,5 à 2 millions de dollars pour une centrale au charbon. Les investisseurs se sont également plaints du prix relativement bas offert par la compagnie d’électricité d’Etat pour acheter de l’électricité produite à partir d’une installation géothermique et qui, selon eux, ne couvre pas la dépense initiale.

Pour couronner le tout, la bureaucratie compliquée de l’Indonésie réduit à néant de nombreux projet. 29 permis sont exigés de différents organismes gouvernementaux et ministères pour la construction d’une centrale géothermique. Les longues négociations avec de puissantes administrations locales peuvent également entraver le projet. L’article donne l’exemple d’une exploration géothermique qui a commencé sur un site en 1985 ; il a fallu attendre 15 ans pour que l’usine a commencé commercialiser de l’électricité. Les travaux sur une nouvelle unité pour accroître la production d’électricité ont été retardés en raison de négociations sur le coût .

Source : Phys.org.

————————————

Indonesia, with scores of volcanoes, holds an estimated 40 percent of the world’s geothermal energy reserves, but has long lagged behind in its use of the renewable power source.

Indonesia, with scores of volcanoes, holds an estimated 40 percent of the world’s geothermal energy reserves, but has long lagged behind in its use of the renewable power source.

Now the government is pushing to expand the sector five-fold in the next decade, although the challenges are huge in a country where the burden of red tape remains onerous, big projects are often delayed and targets missed.

The majority of Indonesia’s power is generated from its abundant reserves of coal and oil. It currently has installed capacity to produce about 1,400 megawatts of electricity from geothermal, enough to provide power to just 1.4 million households in the country off 255 million. That is less than five percent of geothermal’s estimated potential and behind the world’s two leading producers of the energy source, the United States and the Philippines.

But the government is aiming to increase Indonesia’s generating capacity to around 7,200 megawatts by 2025, as part of a broader plan to boost the renewables sector.

A major part of the drive is a law passed two years ago that means geothermal exploration is no longer considered mining activity, as it was previously. The old definition had held up the industry as mining cannot be carried out in the country’s vast tracts of protected forests, believed to contain about two-thirds of Indonesia’s geothermal reserves.

The government is also seeking to sweeten local administrations by offering them up to one percent of revenue from any geothermal plant in their area.

Still, the challenges are enormous. While achieving the 2025 target may be possible, it will be extremely difficult. One of the biggest problems is the high exploration costs needed at the outset, as checking for potential geothermal reserves is a complex, time-consuming business, that is not always successful. Building a geothermal plant costs the equivalent of $4 to $5 million dollars per megawatt, compared to $1.5 to $2 million for a coal-fired power station. Investors have also complained about what they say is the relatively low price offered by the state-run power company to buy electricity from a geothermal facility, which they claim usually doesn’t cover the large initial outlay.

To top it all, Indonesia’s complicated bureaucracy puts many projects off. 29 permits are required from different government agencies and ministries for a geothermal plant, and time-consuming negotiations with powerful local administrations can also hamper progress. The article gives the example of an exploration that first began at a site in 1985 but it was not until 15 years later that the plant began producing electricity commercially, while work on a new unit to boost power generation has been delayed due to negotiations over cost.

Source: Phys.org.

Source: USGS.

Après s’être réveillé en juillet 1995, le volcan Soufrière Hills a dévasté une grande partie de Montserrat, transformé les deux tiers de l’île en une zone d’exclusion et enfoui Plymouth, l’ancienne capitale, sous une épaisse couche de cendre. Aujourd’hui, le volcan s’est calmé et Montserrat envisage d’utiliser la chaleur du sous-sol comme clé de voûte de son économie pour les années à venir.

Après s’être réveillé en juillet 1995, le volcan Soufrière Hills a dévasté une grande partie de Montserrat, transformé les deux tiers de l’île en une zone d’exclusion et enfoui Plymouth, l’ancienne capitale, sous une épaisse couche de cendre. Aujourd’hui, le volcan s’est calmé et Montserrat envisage d’utiliser la chaleur du sous-sol comme clé de voûte de son économie pour les années à venir. Starting in July 1995, the eruption of the Soufriere Hills devastating a large part of Montserrat, leaving two-thirds of the Caribbean island an exclusion zone and Plymouth, the former capital city, buried deep in ash. Today, the volcano has quietened down and Montserrat might now use the volcano’s heat as a key to its future.

Starting in July 1995, the eruption of the Soufriere Hills devastating a large part of Montserrat, leaving two-thirds of the Caribbean island an exclusion zone and Plymouth, the former capital city, buried deep in ash. Today, the volcano has quietened down and Montserrat might now use the volcano’s heat as a key to its future. Volcan Soufriere Hills à Montserrat (Crédit photo: Wikipedia)

Volcan Soufriere Hills à Montserrat (Crédit photo: Wikipedia)