![]() J’ai insisté à plusieurs reprises sur l’importance de la circulation méridienne de retournement de l’Atlantique (AMOC) pour réguler le climat et sur ce qui se passerait si cet énorme tapis roulant cessait de fonctionner. Dans une étude récente publiée dans Science Advances, des scientifiques ont identifié le moteur océanique qui joue le plus grand rôle dans la gestion des principaux courants atlantiques qui régulent le climat de la Terre.

J’ai insisté à plusieurs reprises sur l’importance de la circulation méridienne de retournement de l’Atlantique (AMOC) pour réguler le climat et sur ce qui se passerait si cet énorme tapis roulant cessait de fonctionner. Dans une étude récente publiée dans Science Advances, des scientifiques ont identifié le moteur océanique qui joue le plus grand rôle dans la gestion des principaux courants atlantiques qui régulent le climat de la Terre.

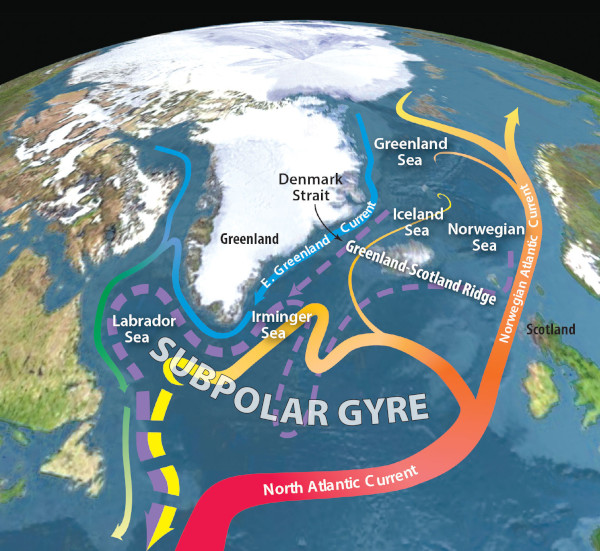

La mer d’Irminger, au sud-est du Groenland, est l’endroit où arrivent les eaux chaudes qui transportent la chaleur vers le nord depuis l’hémisphère sud, puis retournent vers le sud en s’enfonçant le long du fond de l’océan. En tant que telle, cette région joue un rôle essentiel dans le fonctionnement de l’AMOC. L’étude explique qu’il est urgent de mieux surveiller cette zone particulière.

L’AMOC, qui comprend le Gulf Stream, maintient un climat tempéré dans l’hémisphère nord et régule les conditions météorologiques à travers le monde. Toutefois, en raison du réchauffement climatique, l’AMOC pourrait ne pas maintenir les températures stables très longtemps. Les recherches montrent qu’en se déversant dans l’Atlantique Nord, l’eau de fonte de l’Arctique réduit la densité des eaux de surface et les empêche de s’enfoncer pour former des courants de fond. Cette situation ralentit le processus qui alimente l’AMOC.

La mer d’Irminger est particulièrement importante pour maintenir ces courants de fond. On peut lire dans l’étude que « l’arrivée d’eau douce dans cette région non seulement inhibe directement la formation d’eau profonde – essentielle pour maintenir la force de l’AMOC – mais cela modifie également les schémas de circulation atmosphérique. » Une réduction de la quantité d’eau qui s’enfonce dans la mer d’Irminger a probablement des impacts plus importants sur le climat de la planète que des réductions du même type dans d’autres mers du nord.

La mer d’Irminger a une influence très forte sur la force de l’AMOC car elle régule la quantité d’eau qui s’enfonce pour former des courants profonds dans les mers voisines par le biais de processus atmosphériques. L’apport d’eau douce dans la mer d’Irminger améliore le flux d’eau douce dans la Mer du Labrador entre le sud-ouest du Groenland et la côte du Canada, par exemple. Une réduction importante de la formation de courants profonds dans la mer d’Irminger aura des effets en cascade sur la formation de courants profonds dans tout l’Atlantique Nord.

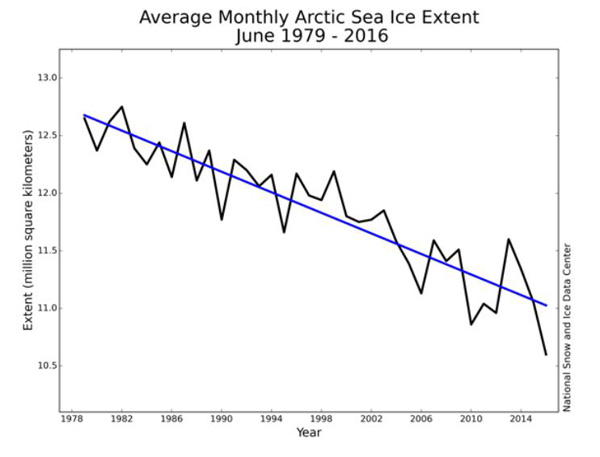

Les auteurs de l’étude ont examiné l’impact de l’eau de fonte sur l’AMOC à l’aide d’un modèle climatique qui simulait une augmentation de l’apport d’eau douce dans quatre régions : la mer d’Irminger, la Mer du Labrador, les mers nordiques et l’Atlantique Nord-Est. Les chercheurs ont pu détecter la sensibilité de l’AMOC à l’eau de fonte dans chaque région, puis ils ont identifié des changements spécifiques du climat de la planète liés à chaque scénario. Le rôle de la mer d’Irminger pour l’AMOC a dépassé celui des trois autres régions du modèle et a déclenché des réactions climatiques plus fortes. La réduction de la formation d’eau profonde a entraîné un refroidissement généralisé dans l’hémisphère nord, ainsi qu’une expansion de la glace de mer arctique, car l’eau chaude n’arrivait plus en provenance du sud.

La simulation a également montré un léger réchauffement dans l’hémisphère sud et a confirmé les conclusions précédentes selon lesquelles un AMOC plus faible perturbait très fortement les systèmes de mousson tropicale.

Source : Live Science via Yahoo News.

Vue des courants océaniques dans la mer d’Irminger (Source : Oceanography)

—————————————————-

![]() I have insisted several times on the importance of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) to regulate the climate and what would happen if this huge conveyor belt stopped working. In a recent study published in Science Advances, scientists have pinpointed the ocean engine with the biggest role in driving key Atlantic currents that regulate Earth’s climate.

I have insisted several times on the importance of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) to regulate the climate and what would happen if this huge conveyor belt stopped working. In a recent study published in Science Advances, scientists have pinpointed the ocean engine with the biggest role in driving key Atlantic currents that regulate Earth’s climate.

The Irminger Sea off southeastern Greenland is where warm waters that transport heat northwards from the Southern Hemisphere sink and then return south along the bottom of the ocean. As such, this region plays a critical role in powering the AMOC. The study highlights the urgent need for better monitoring in this particular location.

The AMOC, which includes the Gulf Stream, maintains a temperate climate in the Northern Hemisphere and regulates weather patterns across the globe. But due to climate change, the AMOC may not keep temperatures stable for much longer. Research shows that Arctic meltwater gushing into the North Atlantic is reducing the density of surface waters and preventing them from sinking to form bottom currents, thus slowing the machine that powers the AMOC.

It turns out the Irminger Sea is particularly important for keeping these bottom currents flowing. One can read in the study that « freshwater release in this region not only directly inhibits deep-water formation — essential for maintaining the strength of the AMOC — but also alters atmospheric circulation patterns. » A reduction in the amount of water sinking in the Irminger Sea likely has greater impacts on the global climate than reductions of the same kind in other northern seas.

The Irminger Sea has a disproportionate influence on the strength of the AMOC because it regulates the amount of water sinking to form deep currents in nearby seas through atmospheric processes. Freshwater input into the Irminger Sea enhances freshwater flow into the Labrador Sea between southwestern Greenland and the coast of Canada, for example, so a reduction in deep-current formation in the Irminger Sea has knock-on effects for deep-current formation across the entire North Atlantic.

The authors of the study examined the impact of meltwater on the AMOC using a climate model that simulated an increase in freshwater input in four regions : the Irminger Sea, the Labrador Sea, the Nordic Seas and the Northeast Atlantic. The researchers were able to detect the sensitivity of the AMOC to meltwater in each region, then identified specific changes in the global climate linked to each scenario. The role of the Irminger Sea for the AMOC outweighed that of the three other regions in the model and triggered stronger climate responses. Reduced deep-water formation led to widespread cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, as well as Arctic sea ice expansion, because warm water was not being brought up from the south.

The simulation also showed slight warming in the Southern Hemisphere and bolstered previous findings that a weaker AMOC would throw tropical monsoon systems into chaos.

Source : Live Science via Yahoo News.