L’éruption du volcan Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai le 15 janvier 2022 a été si violente qu’elle a envoyé des ondes de choc à travers quasiment la moitié du globe terrestre. Le site The Conversation apporte des informations très intéressantes sur l’éruption proprement dite et sur l’histoire de ce volcan.

L’éruption du volcan Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai le 15 janvier 2022 a été si violente qu’elle a envoyé des ondes de choc à travers quasiment la moitié du globe terrestre. Le site The Conversation apporte des informations très intéressantes sur l’éruption proprement dite et sur l’histoire de ce volcan.

Le volcan se compose de deux petites îles inhabitées, Hunga-Ha’apai et Hunga-Tonga qui s’élèvent à une centaine de mètres au-dessus du niveau de la mer, à 65 km au nord de la capitale des Tonga, Nuku’alofa. Mais sous la surface de la mer se cache un volcan beaucoup plus imposant, d’environ 1800 m de hauteur et 20 km de largeur.

Le volcan Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai est entré en éruption régulièrement au cours des dernières décennies. Lors des éruptions de 2009 et 2014-2015, il a propulsé d’impressionnantes gerbes cypressoïdes typiques des éruptions phréato-magmatiques. Cependant, ces éruptions étaient mineures et ont été largement éclipsées par les événements de janvier 2022. Si on se réfère à l’histoire du volcan, il semble que la dernière éruption majeure fasse partie d’une série d’événements qui se produisent environ tous les mille ans.

L’éruption de 2014-2015 a créé un cône volcanique qui a réuni les deux anciennes îles Hunga pour créer une île double d’environ 5 km de long.

Source: NASA

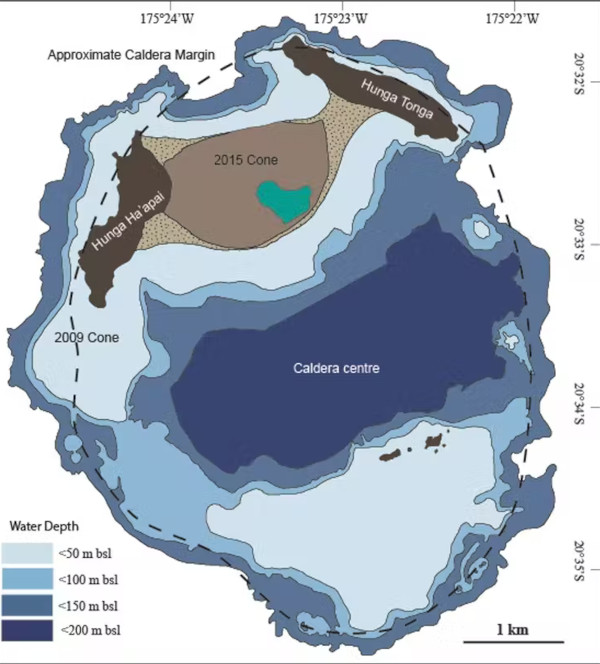

Lorsque les scientifiques ont cartographié le plancher océanique en 2016, ils ont découvert une caldeira qui se cache à 150 mètres de profondeur sous la surface de la mer. La caldeira mesure environ 5 km de diamètre.

Source: The Conversation

Les éruptions mineures (comme celles de 2009 et 2014-2015) se produisent principalement au bord de la caldeira, mais les très grosses éruptions naissent au coeur de la caldeira proprement dite. Ces grandes éruptions sont si importantes que le sommet de la colonne magmatique s’effondre vers l’intérieur de la caldeira et contribue à son approfondissement.

En étudiant la chimie des éruptions passées, on se rend compte que les éruptions mineures correspondent à la lente recharge du système magmatique et annonce le déclenchement d’un événement majeur.

Les scientifiques ont trouvé des preuves de deux énormes éruptions passées de la caldeira Hunga dans des dépôts sur les anciennes îles. Ils ont comparé les analyses chimiques de ces dépôts à des échantillons de cendres prélevés sur la plus grande île habitée de Tongatapu, à 65 km, puis ont utilisé des datations au Carbone 14; il s’avère que de grandes éruptions se produisent dans la caldeira environ tous les 1000 ans, la dernière ayant eu lieu vers 1100. Il semble donc que l’éruption du 15 janvier 2022 soit en plein dans le cycle des événements majeurs.

Les auteurs de l’article de The Conversation ont tenté de prévoir ce qui pourrait arriver par la suite à Hunga-Ha’apai et Hunga-Tonga. Les deux éruptions du 20 décembre 2021 et du 13 janvier 2022 étaient modérées. Elles ont généré des panaches qui se sont élevés jusqu’à 17 km et ont agrandi l’île double qui était apparue en 2014-2015.

La dernière éruption a montré une autre échelle de grandeur. Le panache de cendres est monté à environ 20 km de hauteur. Il s’est étendu de manière concentrique sur une distance d’environ 130 km par rapport au volcan, créant un panache de 260 km de diamètre. Cela démontre une énorme puissance explosive qui ne peut être expliquée par la seule interaction entre le magma et l’eau de mer. Cela montre que de grandes quantités de magma juvénile chargé de gaz se sont échappées de la caldeira.

Source: Tonga Services

L’éruption a également produit un tsunami à travers les Tonga et les Fidji et Samoa voisins. Les ondes de choc ont parcouru plusieurs milliers de kilomètres, ont été observées depuis l’espace et enregistrées en Nouvelle-Zélande à environ 2000 km.

Tous ces événements laissent supposer que la grande caldeira Hunga a repris du service. Les vagues de tsunami ont probablement été causées par des glissements de terrain sous-marins et des effondrements de la caldeira

Reste à savoir si l’événement du 15 janvier 2022 est le point culminant de l’éruption. Il représente la libération d’une importante pression magmatique, ce qui peut contribuer à stabiliser le système. Cependant, les dépôts géologiques des éruptions précédentes de ce volcan montrent que chacun des épisodes éruptifs millénaires majeurs de la caldeira incluait de nombreux événements explosifs. Il se pourrait donc que la dernière grande éruption ne soit pas un événement isolé et que de nouveaux épisodes majeurs d’activité se produisent pendant plusieurs semaines, voire des années sur le volcan Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai.

Source : The New Zealand Herald, The Conversation.

————————————————

The Hunga-Ha’apai and Hunga-Tonga eruption of January 15th, 2022 was so violent that it sent shock waves, quite literally, around half the world. The website The Conversation brings very interesting information about the eruption itself and about the history of this volcano.

The Hunga-Ha’apai and Hunga-Tonga eruption of January 15th, 2022 was so violent that it sent shock waves, quite literally, around half the world. The website The Conversation brings very interesting information about the eruption itself and about the history of this volcano.

The volcano consists of two small uninhabited islands, Hunga-Ha’apai and Hunga-Tonga, rising about 100 m above sea level 65 km north of Tonga’s capital Nuku‘alofa. But hiding below the waves is a massive volcano, around 1800 m high and 20 km wide.

The Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai volcano has erupted regularly over the past few decades. During eruptions in 2009 and 2014-2015, the volcano sent impressive cypressoid sheaves typical of phreato-magmatic eruptions. However, these eruptions were small and dwarfed in scale by the January 2022 events. Looking at the history of the volcano, it looks as if the last eruption is one of the massive explosions the volcano is capable of producing roughly every thousand years.

The 2014-2015 eruption created a volcanic cone, joining the two old Hunga islands to create a combined island about 5km long.

When scientists mapped the sea floor in 2016, they discovered a hidden caldera 150 meters below the waves. The caldera is about 5 km across. Small eruptions (such as in 2009 and 2014-2015) occur mainly at the edge of the caldera, but very big ones come from the caldera itself. These big eruptions are so large the top of the erupting magma collapses inward, deepening the caldera.

Looking at the chemistry of past eruptions, it is thought the small eruptions represent the magma system slowly recharging itself to prepare for a big event.

Scientists found evidence of two huge past eruptions from the Hunga caldera in deposits on the old islands. They matched these chemically to volcanic ash deposits on the largest inhabited island of Tongatapu, 65 km away, and then used radiocarbon dates to show that big caldera eruptions occur about ever 1000 years, with the last one at AD1100. With this knowledge, the eruption on January 15th, 2022 seems to be right on schedule for a major event.

The authors of the article in The Conversation tried to figure out what could happen next at Hunga-Ha’apai and Hunga-Tonga. The two earlier eruptions on December 20th, 2021 and January 13th, 2022 were of moderate size. They produced clouds that rose up to 17 km and added new land to the 2014-2015 combined island.

The latest eruption has stepped up the scale in terms of violence. The ash plume is already about 20 km high. It spread out almost concentrically over a distance of about 130 km from the volcano, creating a plume with a 260 km diameter, before it was distorted by the wind. This demonstrates a huge explosive power which cannot be explained by magma-water interaction alone. It shows instead that large amounts of fresh, gas-charged magma have erupted from the caldera.

The eruption also produced a tsunami throughout Tonga and neighbouring Fiji and Samoa. Shock waves traversed many thousands of kilometres, were seen from space, and recorded in New Zealand some 2000 km away.

All these signs suggest the large Hunga caldera has awoken. The tsunami waves may have been caused by submarine landslides and caldera collapses

It remains unclear if this is the climax of the eruption. It represents a major magma pressure release, which may settle the system. However, the geological deposits from the volcano’s previous eruptions show that each of the 1000-year major caldera eruption episodes involved many separate explosion events. Hence, the last big eruption might not be an isolated event and we could be in for several weeks or even years of major volcanic unrest from the Hunga-Tonga-Hunga-Ha’apai volcano.

Source: The New Zealand Herald, The Conversation.