![]() J’ai écrit plusieurs notes sur ce blog à propos de l’affaiblissement de l’AMOC, autrement dit la circulation méridienne de renversement de l’Atlantique, par exemple le 17 avril 2018, le 3 août 2020, ou encore le 8 août 2021. Aujourd’hui, les scientifiques pensent que « l’océan Atlantique se dirige vers un point de non-retour avec le Gulf Stream. » C’est le titre d’un article publié sur le site The Conversation. Les chercheurs craignent que le réchauffement climatique puisse arrêter la circulation méridionale de retournement de l’Atlantique, essentielle au transport de la chaleur des tropiques vers les latitudes septentrionales. Un tel arrêt aurait inévitablement de graves conséquences.

J’ai écrit plusieurs notes sur ce blog à propos de l’affaiblissement de l’AMOC, autrement dit la circulation méridienne de renversement de l’Atlantique, par exemple le 17 avril 2018, le 3 août 2020, ou encore le 8 août 2021. Aujourd’hui, les scientifiques pensent que « l’océan Atlantique se dirige vers un point de non-retour avec le Gulf Stream. » C’est le titre d’un article publié sur le site The Conversation. Les chercheurs craignent que le réchauffement climatique puisse arrêter la circulation méridionale de retournement de l’Atlantique, essentielle au transport de la chaleur des tropiques vers les latitudes septentrionales. Un tel arrêt aurait inévitablement de graves conséquences.

Au cours des dernières années, à partir de 2004, les instruments ont montré que la circulation du Gulf Stream dans l’océan Atlantique a considérablement ralenti, atteignant peut-être son état le plus faible depuis près d’un millénaire. Des études montrent également que la circulation a déjà atteint un point de basculement dans le passé et qu’elle pourrait à nouveau l’atteindre à mesure que la planète se réchauffe et que les glaciers et les calottes glaciaires fondent.

Dans une nouvelle étude utilisant des modèles climatiques dernière génération, les scientifiques ont simulé la circulation de l’eau douce dans l’océan jusqu’à ce qu’elle atteigne ce point de non-retour. Les résultats montrent que la circulation pourrait s’arrêter complètement d’ici un siècle après avoir atteint le point de basculement, et qu’elle se dirige désormais dans cette direction. Si ce point critique était atteint, les températures moyennes chuteraient de plusieurs degrés en Amérique du Nord, dans certaines parties de l’Asie et de l’Europe, et les populations subiraient des conséquences graves et en cascade dans le monde entier.

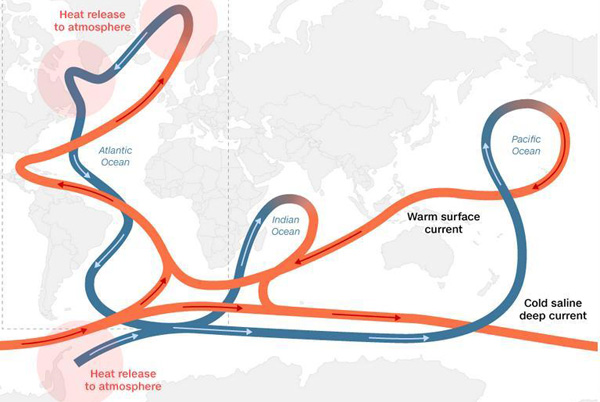

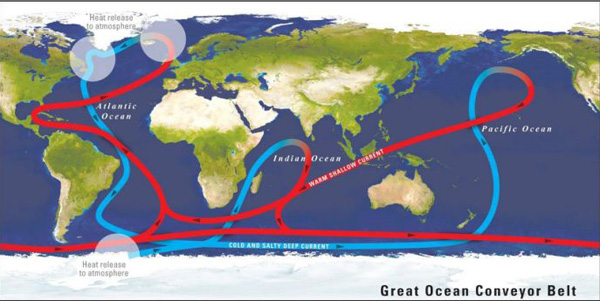

Dans la circulation de l’océan Atlantique, les eaux de surface relativement chaudes et salées proches de l’équateur s’écoulent vers le Groenland. Au cours de ce voyage, elles traversent la mer des Caraïbes, remontent dans le golfe du Mexique, puis longent la côte est des États-Unis avant de traverser l’Atlantique. Ce courant, le Gulf Stream, apporte de la chaleur en Europe. À mesure qu’elle s’écoule vers le nord et se refroidit, la masse d’eau devient plus lourde. Au moment où elle atteint le Groenland, elle commence à s’enfoncer et à se diriger ensuite vers le sud. Au moment où l’eau s’enfonce, il se produit un nouvel apport ailleurs dans l’Atlantique, lançant un cycle qui se répète, comme un tapis roulant.

Une trop grande quantité d’eau douce provenant de la fonte des glaciers et de la calotte glaciaire du Groenland fait baisser la salinité de l’eau et donc l’empêche de s’enfoncer, ce qui affaiblit l’énergie du tapis roulant océanique. Il s’ensuit un engrenage : un tapis roulant plus faible transporte moins de chaleur vers le nord et permet également à moins d’eau plus lourde d’atteindre le Groenland, ce qui affaiblit encore davantage la force du tapis roulant. Une fois atteint le point de basculement, le tapis roulant s’arrête rapidement. La dernière étude a révélé qu’il pourrait s’arrêter d’ici une centaine d’années.

Si le Gulf Stream s’arrêtait, cela ferait chuter la température de quelques degrés sur les continents nord-américain et européen. Selon l’étude, certaines parties du continent se refroidiraient de plus de 3 degrés Celsius par décennie, bien plus rapidement que le réchauffement climatique actuel qui est d’environ 0,2 degré Celsius par décennie. En revanche, les régions de l’hémisphère sud se réchaufferaient de quelques degrés. Ces changements de température s’étaleraient sur une centaine d’années.

L’arrêt du tapis roulant affecterait également le niveau de la mer et la configuration des précipitations. Par exemple, la forêt amazonienne est vulnérable à la baisse des précipitations. Si son écosystème forestier se transformait en prairies, la transition libérerait du carbone dans l’atmosphère et entraînerait la perte d’un précieux puits de carbone, accélérant ainsi le réchauffement climatique.

L’AMOC s’est déjà considérablement ralenti dans un passé lointain. Lorsque les calottes glaciaires qui recouvraient une grande partie de la planète fondaient, l’apport d’eau douce ralentissait la circulation atlantique, déclenchant d’énormes fluctuations climatiques.

La grande question est de savoir quand la circulation atlantique atteindra un point de basculement et donc de non-retour. Personne n’a la réponse. Les observations ne remontent pas assez loin dans le temps pour fournir un résultat clair. Une étude récente explique que le tapis roulant approche rapidement de son point de basculement, peut-être d’ici quelques années, mais les analyses statistiques ont formulé plusieurs hypothèses qui laissent planer le doute.

———————————————

![]() I have written several posts on this blog about the weakening of the AMOC, like on 17 April 2018, 3 August 2020, 8 August 2021). Today, scientists think that « the Atlantic Ocean is headed for a tipping point in the Gulf Stream. » This is the title of an arpicle published on the website The Conversation. Scientists fear that global warming may shut down the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) which is crucial for carrying heat from the tropics to the northern latitudes. Such a shutdown would inevitably have severe consequences.

I have written several posts on this blog about the weakening of the AMOC, like on 17 April 2018, 3 August 2020, 8 August 2021). Today, scientists think that « the Atlantic Ocean is headed for a tipping point in the Gulf Stream. » This is the title of an arpicle published on the website The Conversation. Scientists fear that global warming may shut down the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) which is crucial for carrying heat from the tropics to the northern latitudes. Such a shutdown would inevitably have severe consequences.

Over the past few years, starting in 2004, instruments deployed in the ocean have shown that the Atlantic Ocean circulation has slowed over the past two decades, possibly to its weakest state in almost a millennium. Studies also suggest that the circulation reached a dangerous tipping point in the past and that it could hit that tipping point again as the planet warms and glaciers and ice sheets melt.

In a new study using the latest generation climate models, scientists have simulated the flow of fresh water until the ocean circulation reached that tipping point. The results show that the circulation could fully shut down within a century after hitting the tipping point, and that it is now headed in that direction. If that tipping point was reached, average temperatures would drop by several degrees in North America, parts of Asia and Europe, and people would see severe and cascading consequences around the world.

In the Atlantic Ocean circulation, the relatively warm and salty surface water near the equator flows toward Greenland. During its journey, it crosses the Caribbean Sea, loops up into the Gulf of Mexico, and then flows along the U.S. East Coast before crossing the Atlantic. This current, the Gulf Stream, brings heat to Europe. As it flows northward and cools, the water mass becomes heavier. By the time it reaches Greenland, it starts to sink and flow southward. The sinking of water near Greenland pulls water from elsewhere in the Atlantic Ocean and the cycle repeats, like a conveyor belt.

Too much fresh water from melting glaciers and the Greenland ice sheet can dilute the saltiness of the water, preventing it from sinking, and weaken this ocean conveyor belt. A weaker conveyor belt transports less heat northward and also enables less heavy water to reach Greenland, which further weakens the conveyor belt’s strength. Once it reaches the tipping point, it shuts down quickly.The latest study found that the conveyor belt may shut down within 100 years.

Should the Gulf Stream stop, it wouldcool the North American and European continents by a few degrees. According to the study, parts of the continent would cool by more than 3 degrees Celsius per decade, far faster than today’s global warming of about 0.2 degrees Celsius per decade. On the other hand, regions in the Southern Hemisphere would warm by a few degrees. These temperature changes would develop over about 100 years.

The conveyor belt shutting down would also affect sea level and precipitation patterns. For example, the Amazon rainforest is vulnerable to declining precipitation. If its forest ecosystem turned to grassland, the transition would release carbon to the atmosphere and result in the loss of a valuable carbon sink, further accelerating climate change.

The Atlantic circulation already slowed significantly in the distant past. During glacial periods when ice sheets that covered large parts of the planet were melting, the influx of fresh water slowed the Atlantic circulation, triggering huge climate fluctuations.

The big question — when will the Atlantic circulation reach a tipping point ? — remains unanswered. Observations don’t go back far enough to provide a clear result. While a recent study suggested that the conveyor belt is rapidly approaching its tipping point, possibly within a few years, the statistical analyses made several assumptions that give rise to uncertainty.